“I remember very, very clearly a shot into each of my friends,” says William T. Vollmann, about the brutal end to a road trip he took through Bosnia for SPIN thirty years ago. (Credit: Philippe Merle/AFP/GettyImages)

In this ongoing series, we revisit some of our most memorable moments with SPIN’s journalists, photographers, and editors.

To our knowledge, William T. Vollmman is the only alumni of SPIN’s revolving madhouse of journalists whom the FBI deemed a “viable suspect” in the Unabomber case.

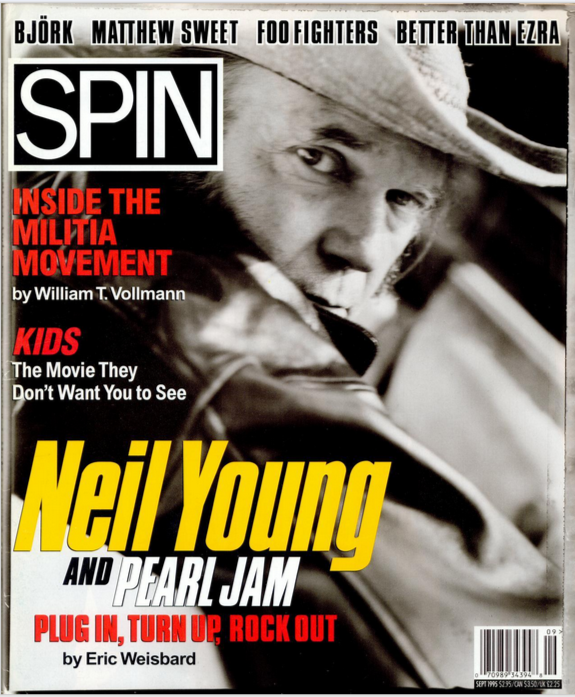

Following a tip that our intrepid reporter might be America’s pre-eminent Luddite philosopher-terrorist of the late 20th Century, murdering three and injuring 23 in a decades-long bombing campaign which overlapped with his time at SPIN, Vollmann was closely read by the feds.

Suspect S-2047, as the FBI labeled Vollmann, was declared “armed and dangerous” (reportedly even owning a flamethrower along with all his guns), a crackhead, placed under surveillance, and warranted a file of almost 800 pages.

That’s our Bill! Not for us the people-pleasing puff-piecing ’content creators’ who could be replaced overnight by AI and no one would fucking know or care. We hate music like that and we hate writing like that. Our first question when vetting prospective journalists is: where’s your flamethrower, crackhead?

Hence Vollmann, with his pre-SPIN resume highlight of getting the runs with the mujahadeen, fit the bill.

Nonetheless, while the man who recruited the intrepid Vollmann for SPIN—founder Bob Guccione Jr.—most certainly did not rat on Vollmann to the FBI, at the time he privately wondered if Bill was the mad bomber.

“The thought did cross my mind,” says Guccione (whose father, Robert Guccione, was in 1995 negotiating with the Unabomber about writing a column for his magazine, Penthouse). Vollmann and the Luddite extremist, says Bob, were “not a million miles away ideologically.”

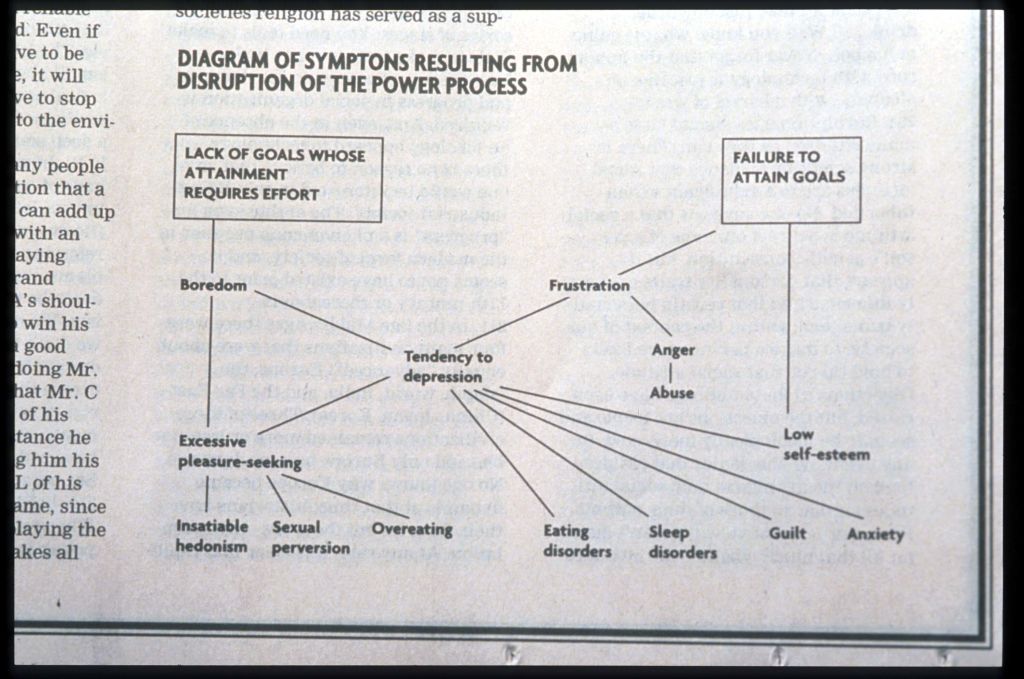

Nor in terms of filing hefty copy, Exhibit A being the Unabomber’s 35,000-word treatise, “Industrial Society and its Future,” which the Washington Post published with the terrorist still at large, and Exhibit B being Vollmann’s drafts.

Guccione explains: “It wasn’t an email you’d get. It wasn’t a story in a Google doc. This was a story in a brown manila envelope—a thick envelope—and it’d be 20,000, 30,000 words. And handwritten. We’d have to type it up. Once it was 80,000 words, and I said to him: ‘I’m not even going to read this.’”

Back in the 1990s, when SPIN was low-tech even for its time, the sheer length of Vollmann’s dispatches made for a hell of a lot of wrangling to get them onto the page.

“It was all done by hand and the process was primitive,” says Bob. “I’d have to get them typed up and then the editing was done with a pen on a printed sheet. You’d X out things you didn’t want and write questions you had in red. And post it back. And then when the stories come back again you’re still dealing with that many thousands of words that you can have problems fitting it all because of line breaks, paragraph breaks, dialogue, and all that. It’s not like online where you can just make things fit,” Bob says. “We’d have to go in and sometimes edit it with a scalpel—physically cutting out words to make it fit the layout.”

The feds figured Bill might be their boy, not only because of his dodgy travels (sorry, Bill, for the eyebrow-raising assignments), love of hand-crafting objects (as the bombs were), or his “strong physical resemblance to UNABOMBER composites,” but due to what they gleaned from his writing. Vollmann’s oeuvre, wrote an FBI agent, is an expression of “anti-progress, anti-industrialist themes/beliefs/value systems.”

It’s debatable, I guess, whether an enthusiasm for flamethrowers is pro or anti-industrial, but one thing Bill most certainly was at SPIN, however, was anti-bullshit. Or, to put it another way, anti group-think.

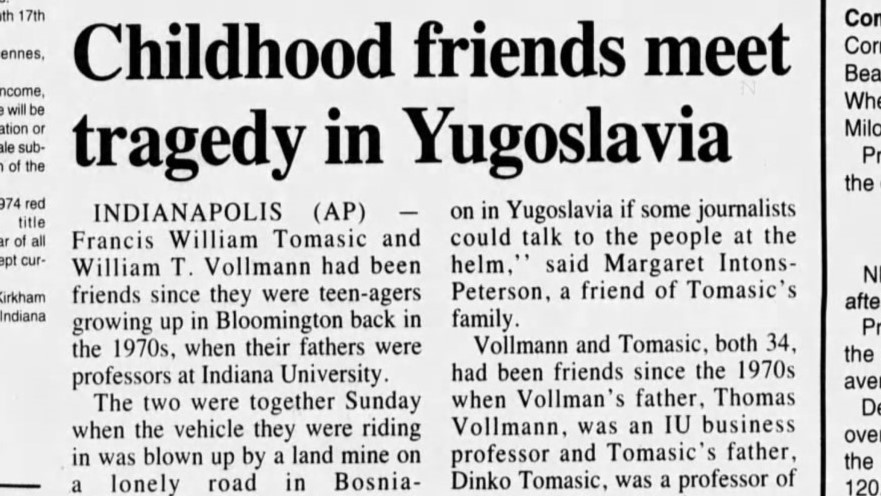

So in 1994 when Bob sent Bill and, at Vollmann’s request, his Serbo-Croatian speaking schoolmate-and-college-mate-turned-photographer Francis Tomasic to the war in the former Yugoslavia, they did not come back with some rinse-and-repeat, fixer-programmed, write-by-numbers piece that any hack with a visa and PRESS vest could have churned out.

Francis, heartbreakingly, didn’t come back at all.

The SPIN duo were driving through a Bosnian-government held area near Mostar with another American, Bryan Brinton, in a rented Peugeot, when, according to the U.N., they triggered a landmine, while Vollmann asserts that gunmen opened up on them. From his subsequent SPIN article:

The first explosion smashed through the windshield. . . . I can no longer remember whether the second explosion came just before or just after Francis’s two screams, short and shrill and horrible with what I took at that moment to be only panic … I heard soldiers shouting something from the Muslim side, and then there was laughter.

Vollmann, who doesn’t drive due to being too visually impaired, had been dozing in the back seat. He woke as the sole survivor, with Tomasic dead at 36; Brinton, who’d served as a medic in Vietnam and now wanted to be a war photographer, at 44. The pair were the 67 and 68th journalists killed in the conflict, according to the BBC.

“I had asked him not to bring Francis,” says Guccione. “He wanted to bring him from America as an interpreter and I said don’t do that—find someone locally who knows the lay of the land. It’ll be safer for both of you. But Bill said, ‘Oh no, no, it’s okay.’ And in the end I gave Bill what he wanted, because that was the spirit of our relationship,” says Guccione.

“I don’t know if it would have made a difference because they just drove over a mine, but I didn’t want him to bring that kid. I always feel very bad about that. I feel very, very sad about it to this day.”

After the lethal mishap, Guccione told Vollmann to come home, but Vollmann—distraught as he was—wanted to stay and finish the job. Which he did.

I have a very, very strong hatred for authority. Vollmann

And in the astonishing story that he filed, “The Way Never Came Here,” the horrendous event Bill survived just happens, and it does so thousands of words into the article without any laborious setting up or foreshadowing. Much like anyone else’s killing in those years—it just happens.

As recounted in the story (published in the November ‘94 issue), after Bill gets his nerve up to deal with the militiamen who surround the stricken car, and then eventually gets evacuated by Spanish peacekeepers, he continues his exploration, and from that point in the article, the personal disaster, the killing of his comrades, both does and does not dominate the article as a whole.

“I’d known from the very first that my two friends had died for nothing because this war had not been theirs, and […] whatever had killed them, did so really by ‘mistake’,” Vollmann writes later in the piece. “But more and more I started thinking everyone else had died for nothing, too.”

And in the narrative, he thinks this in the company of Serbs—the American government’s and much of the press’ designated villains. For in general, regardless of their ways and walks, their complicity or circumstance, Bill is about opening to people, listening to people, drinking with them (even doing crack with them or buying sex from them), and respecting readers’ ability to think for themselves, rather than being about ignoring or concealing his subjects’ reality, their human mess, by pasting over it two-dimensional masks issued by U.S. Central Casting or anyone else.

Post-SPIN, in 2002 as the U.S. war machine set its sights on Iraq, Vollmann gives a speech titled: “Some Thoughts on the Value of Writing During Wartime.” In it, Bill says that he was not necessarily opposed to the impending U.S. invasion of Iraq—a country he had visited as a journalist—but that to endorse it he would need a more convincing narrative than the U.S. government had so far supplied.

To Vollmann, Saddam Hussein and the Iraqis were being presented to Americans as “flat characters”—like villains and victims in crime fiction. Vollmann’s complaint is that crime fiction is a genre which does not aim to capture the unpredictable, unresolvable, often counter-intuitive nature of reality, but instead seeks to slot people in to serve the plot—like governments and their lackeys in the press uninterested in the mess and nuance of life and history, but very interested in moving the story toward a predetermined result.

Bill at SPIN was into the mess—into the rugged topography of the human spirit. And it was mess—whether captured by Bill in his reportage or by our music writers in their decidedly non PR-mindful coverage of a routinely, obscenely, boringly airbrushed industry—that made SPIN great.

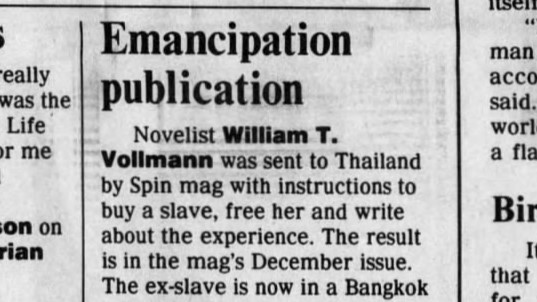

“For his first article for us,” recalls Guccione, “he suggested going to Thailand to free a sex slave. He might not have thought I’d go for it, but I went for it in a heartbeat. I said, ‘Brilliant idea. Good luck. Keep your head down.’ And that began that fantastic, wonderful adventure together which lasted several years.”

That first story of Vollmann’s, “Sex Slave,” in which he buys an underage girl from a horrible brothel in Ranong province, on Myanmar’s southern border, before delivering her to a women’s refuge and training center in Bangkok, made a splash when it hit the stands in the December ‘93 issue.

And in that late, great decade of print, back before the internet hit magazine and newspaper revenue and staffing as hard as Ted Bundy on a sorority house, SPIN was selling upwards of half a million copies per issue. Guccione’s upstart mag had won the devoted readership of young and freethinking pop culture lovers who wanted not only to be informed, but challenged, surprised, shocked, even at times—oh my lord—affronted!, but never taken for granted nor pandered to.

“Our advertising revenue was in the millions—millions per month,” says Guccione, with the expenses for Vollmann’s stories running up to $30,000 apiece. “It was massive money, because he’d be gone for a month. He never lived high on the hog—he’d stay in $6 a night hotels and eat $2 meals—but he did buy a prostitute. He did bribe people all the time. We spent whatever he needed. We gave him the money and freedom to do whatever he wanted. It was limitless,” Guccione says. “But Bill never took advantage. He was honest.” The accounting side gave the office back in New York some chuckles: “My CFO would come walking into my office and go, ‘I’ve got another expense from Bill.’ It would literally say: ‘Prostitute, $25.’ His were the only expense reports I ever saw that listed prostitutes as a legitimate expense. And it wasn’t just that one story—he had a thing for prostitutes.”

Vollmann’s journalistic endeavors were not the costliest, though. For “Inside the IRA,” SPIN-reporter Rory Nugent’s account of clandestinely meeting in Northern Ireland the insurgent group’s Sergeant-at-Arms, Guccione says he laid out between $40,000 and $50,000.

“That era of journalism is gone. We were the last great magazine,” says Bob. “After us there were no more new magazines doing this kind of work, or wanting to do this kind of work, although I’d like to bring some of that back.”

It’s now 30 years since Vollmann returned alone from Bosnia, and 27 since Guccione (who has returned as a consultant) sold SPIN, with the buyers and some subsequent owners more into tidiness than Bill and Bob.

Vollmann went on to establish himself as one of America’s great writers, beating out E.L. Doctorow, Mary Gaitskill, and others to win the 2005 National Book Award with Europe Central, his extraordinary, singular novel of World War II’s vast and vastly brutal eastern theater. What’s more, music lovers, a solid chunk of that phat tome is from the viewpoint of Dmitri Shostakovich, including while the sometimes persecuted, sometimes celebrated Russian composer writes his 7th Symphony in bomb shelters of Leningrad amidst the German-Finnish siege, in which the Axis’ deliberate starvation of the inhabitants kills an estimated one million Russians (with shelling and assaults killing hundreds of thousands more).

Bill’s two-volume autodidactic, experiential, philosophical grappling with what we’re doing to the planet, Carbon Ideologies, published in 2018, was described by the Atlantic as “the most honest book about climate change yet.” My favorite of his many books, however, is his slimmest, Riding Toward Everywhere, a 2008 reflective account of his time hopping freight trains. So as a writer, Vollmann’s done splendidly post-SPIN—writing up a storm for decades and doing so in ways no one else can or would.

Yet, Bill could now be likened to Job: beset by torment, trial, and tragedy. In recent years he has lost much of his intestines to colon cancer; his publisher of almost four decades dropped him in 2022 over his refusal to be edited (a protected status he had previously secured in exchange for reduced royalties, but Viking insisted with a new anchor-weight fiction manuscript), and that same year his daughter’s “protracted dying”—as he describes the wretched state into which she had descended as an alcoholic—finished. Dead in her mid-20s. Bill writes how he then spent a year or so “in bed, staring at the wall.”

For what it’s worth, talking to Vollmann took me more than a decade to arrange. I first asked back in 2008 when I was doing a doctorate (much of which was on Vollmann’s nonfiction). I wrote him a cringey letter asking for an interview.

Vollmann didn’t answer, but many years later I discovered that item 4, folder 62, box 7 of the William T. Vollmann archive at Ohio State University’s Rare Books and Manuscripts Library in Columbus is listed as “Correspondence from Matthew Thompson to WTV, December 31, 2008.”

As part of my doctoral research in 2009 I went to that library in Columbus and scoured those archives, but I don’t think my letter was there at the time. Seems he included it in a later tranche of bumf that OSU has acquired for scholars, obsessives, and posterity. Made me want to write another, somewhat spicier, letter to him, but he probably would have just sold that, too.

His were the only expense reports I ever saw that listed prostitutes as a legitimate expense. Bob Guccione Jr.

A lifetime later, however—my doctorate long completed and my Vollmann obsession having waned into a more sober appreciation of certain aspects of his work—he’s ready to talk. I learn this one midnight when a mutual contact tells me that Vollmann will accept a call in six hours. Bill does not use email, digital media, the internet, or cell phones, but he has a landline locked in a closet with an answering machine attached. At daybreak tomorrow my time, he will unlock the closet and actually pick up the phone when it rings.

Last word before we get into the interview goes to Bob Guccione Jr. “Bottom line,” he says, “is that Bill Vollmann was the greatest writer SPIN has ever published and I was so happy to publish him. I’m very proud to be part of his trajectory.”

(P.S. The real Unabomber, MK-ULTRA alumni Theodore Kaczynski, was caught in 1996 after publication of his manifesto led to his brother recognizing his writing style and contacting the law. Last year Kaczynski killed himself in prison.)

SPIN: Looking back through your writing on prostitution, I came across a kind of sexual reverence for women that a lot of [cis, binary, heterosexual, and perhaps even toxically masculine] men might have an aversion to as misshapen or scarred, and see as ugly. Have you always found yourself sexually aroused by women damaged by the grind and damage of poverty and with all kinds of body shapes?

William T. Vollmann: Yeah, sure. Although sometimes the arousal is attenuated. If you go to the Vatican, and you see some old marble statue of a beautiful goddess, and you think, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s very beautiful, very harmonious. I enjoy looking at the shape.’ Let’s call that sexual arousal. So if I see some maimed old woman covered with abscesses, but she looks at me with her big, beautiful dark eyes full of pain, I’m gonna see her as beautiful. That doesn’t mean that I necessarily want to have sex with her right then, but she is beautiful and attractive to me.

So it’s not always hard-edge, tumescent sexuality?

That would get old if a man felt that about every woman, and there might be a lot of frustration for him.

So the prostitution thing is also the time you spend with people you see as amazing and who embody hard, lived, lives?

A lot of them have been my sisters and teachers and friends. And a lot of them have also been my charity cases, and I’m very proud of that fact.